- Home

- L. M. Montgomery

Anne of Windy Poplars

Anne of Windy Poplars Read online

PUFFIN CLASSICS

ANNE OF WINDY WILLOWS

LUCY MAUDE MONTGOMERY (1874-1942) was born on Prince Edward Island, off the east coast of Canada. She lived there throughout her childhood with her grandparents (following her mother's death in 1876). Readers of the Anne of Green Gables series of books will find plenty of scenes drawn from the author's happy memories of the island and the farmhouse where she was brought up.

Like many a future writer, Lucy Maude Montgomery was not only an avid reader as a child, but also composed numerous short stories and poems. Her first published piece was a poem that appeared in the local paper when she was fifteen years old. Later, after she had finished school and university, she turned her love of books to good effect by becoming a teacher.

She continuted to write, and was once asked to contribute a short story to a magazine. She dusted off an idea for a plot she had jotted down when she was much younger - and turned it into one of the most popular books ever written for children. Anne of Green Gables was first published in 1908.

Lucy herself said about Anne of Green Gables: 'I thought girls in their teens might like it. But grandparents, school and college boys, old pioneers in the Australian bush, girls in India, missionaries in China, monks in remote monasteries, premiers of Great Britain, and red-headed people all over the world have written to me, telling me how they loved Anne and her successors.'

The 'successors' are nine further Anne books, all of which are now published in Puffin Classics. Lucy Maude Montgomery continued to write under her maiden name after marrying a Presbyterian minister, Ewan MacDonald, in 1911. And, despite moving with him to Toronto, she continued to set her stories on 'the only island there is', and where her heart always remained.

Some other Puffin Classics to enjoy

ANNE OF GREEN GABLES

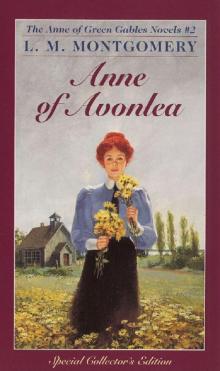

ANNE OF AVONLEA

ANNE'S HOUSE OF DREAMS

ANNE OF INGLESIDE

CHRONICLES OF AVONLEA

RAINBOW VALLEY

L. M. Montgomery

EIGHT COUSINS

GOOD WIVES

JACK AND JILL

JO'S BOYS

LITTLE MEN

LITTLE WOMEN

ROSE IN BLOOM

Louisa M. Alcott

WHAT KATY DID

WHAT KATY DID AT SCHOOL

WHAT KATY DID NEXT

Susan Coolidge

POLLYANNA

POLLYANNA GROWS UP

Eleanor H. Porter

L. M. MONTGOMERY

Anne of Windy Willows

PUFFIN BOOKS

PUFFIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi - 110 017, India Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, Cnr Rosedale and Airborne Roads, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England www.penguin.com

First published in Great Britain by Harrap Limited 1936

Published in Puffin Books 1983

Reissued in this edition 1994

24

Copyright (c) 1936 by L. M. Montgomery All rights reserved

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than than in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser ISBN: 978-0-14-194419-7

To the Friends of Anne Everywhere

CONTENTS

The First Year

The Second Year

The Third Year

THE FIRST YEAR

1

A letter from Anne Shirley, B.A., Principal of Summerside High School, to Gilbert Blythe, medical student at Redmond College, Kingsport

Windy Willows

Spook's Lane

S'side

P.E.I.

Monday, Sept. 12

DEAREST,

Isn't that an address! Did you ever hear anything so delicious? Windy Willows is the name of my new home, and I love it. I also love Spook's Lane, which has no legal existence. It should be Trent Street, but it is never called Trent Street except on the rare occasions when it is mentioned in the Weekly Courier - and then people look at each other and say, 'Where on earth is that?' Spook's Lane it is - although for what reason I cannot tell you. I have already asked Rebecca Dew about it, but all she can say is that it has always been Spook's Lane, and there was some old yarn years ago of its being haunted. But she has never seen anything worse-looking than herself in it.

However, I mustn't get ahead of my story. You don't know Rebecca Dew yet. But you will - oh, yes, you will! I foresee that Rebecca Dew will figure largely in my future correspondence.

It's dusk, dearest. (In passing, isn't 'dusk' a lovely word? I like it better than twilight. It sounds so velvety and shadowy and - and - dusky.) In daylight I belong to the world; in the night to sleep and eternity. But in the dusk I'm free from both and belong only to myself - and you. So I'm going to keep this hour sacred to writing to you. Though this won't be a love-letter. I have a scratchy pen, and I can't write love-letters with a scratchy pen, or a sharp pen, or a stub pen. So you'll only get that kind of a letter from me when I have exactly the right kind of a pen. Meanwhile I'll tell you about my new domicile and its inhabitants. Gilbert, they're such dears.

I came up yesterday to look for a boarding-house. Mrs Rachel Lynde came with me, ostensibly to do some shopping, but really, I know, to choose a boarding-house for me. In spite of my Arts course and my B.A. Mrs Lynde still thinks I am an inexperienced young thing who must be guided and directed and overseen.

We came by train, and, oh, Gilbert, I had the funniest adventure! You know I've always been one to whom adventures came unsought. I just seem to attract them, as it were.

It happened just as the train was coming to a stop at the station. I got up, and, stooping to pick up Mrs Lynde's suitcase - she was planning to spend Sunday with a friend in Summerside - I leaned my knuckles heavily on what I thought was the shiny arm of a seat. In a second I received a violent crack across them that nearly made me howl. Gilbert, what I had taken for the arm of a seat was a man's bald head. He was glaring fiercely at me, and had evidently just wakened up. I apologized abjectly, and got off the train as quickly as possible. The last I saw of him he was still glaring. Mrs Lynde was horrified, and my knuckles are sore yet!

I did not expect to have much trouble in finding a boarding-house, for a certain Mrs Tom Pringle had been boarding the various Principals of the High School for the last fifteen years. But for some unknown reason she has grown suddenly tired of 'being bothered', and wouldn't take me. Several other desirable places had some polite excuse. Several other places weren't desirable. We wandered about the town the whole afternoon, and got hot and tired and blue and headachy - at least, I did. I was ready to give up in despair - and then Spook's Lane just happened!

We had dropped in to see Mrs Braddock, an old crony of Mrs Lynde's, and Mrs Braddock said she thought 'the widows' might take me in.

'I've heard they want a boarder to pay Rebecca Dew's wages. They can't afford to keep Rebecca any longer unless a little extra money comes in. And if Rebecca goes who is to milk that old red cow?'

Mrs Braddock fixed me with a stern e

ye, as if she thought I ought to milk the red cow, but wouldn't believe me on oath if I claimed I could.

'What widows are you talking about?' demanded Mrs Lynde.

'Why, Aunt Kate and Aunt Chatty,' said Mrs Braddock, as if everybody, even an ignorant B.A., ought to know that. 'Aunt Kate is Mrs Amasa MacComber - she's the Captain's widow - and Aunt Chatty is Mrs Lincoln MacLean, just a plain widow. But everyone calls them "Aunt". They live at the end of Spook's Lane.'

Spook's Lane! That settled it. I knew I just had to board with the widows.

'Let's go and see them at once,' I implored Mrs Lynde. It seemed to me if we lost a moment Spook's Lane would vanish back into fairyland.

'You can see them, but it'll be Rebecca who'll really decide whether they'll take you or not. Rebecca Dew rules the roost at Windy Willows, I can tell you.'

Windy Willows! It couldn't be true - no, it couldn't! I must be dreaming. And Mrs Rachel Lynde was actually saying it was a funny name for a place.

'Oh, Captain MacComber called it that. It was his house, you know. He planted all the willows round it, and was mighty proud of it, though he was seldom home and never stayed long. Aunt Kate used to say that was inconvenient, but we never got it figured out whether she meant his staying such a little time or his coming back at all. Well, Miss Shirley, I hope you'll get there. Rebecca Dew's a good cook and a genius with cold potatoes. If she takes a notion to you you'll be in clover. If she don't - well, she won't, that's all. I hear there's a new banker in town looking for a boarding-house, and she may prefer him. It's kind of funny Mrs Tom Pringle wouldn't take you. Summerside is full of Pringles and half-Pringles. They're called the "Royal Family", and you'll have to get on their good side, Miss Shirley, or you'll never get along in Summerside High. They've always ruled the roost hereabouts. There's a street called after old Captain Abraham Pringle. There's a regular clan of them, but the two old ladies at Maplehurst boss the tribe. I did hear they were down on you.'

'Why should they be?' I exclaimed. 'I'm a total stranger to them.'

'Well, a third cousin of theirs applied for the Principalship, and they all think he should have got it. When your application was accepted the whole kit and boodle of them threw back their head and howled. Well, people are like that. We have to take them as we find them, you know. They'll be as smooth as cream to you, but they'll work against you every time. I'm not wanting to discourage you, but forewarned is forearmed. I hope you'll make good just to spite them. If the widows take you, you won't mind eating with Rebecca Dew, will you? She isn't a servant, you know. She's a far-off cousin of the Captain's. She don't come to the table when there's company - she knows her place then - but if you were boarding there she wouldn't consider you company, of course.'

I assured the anxious Mrs Braddock that I'd love eating with Rebecca Dew, and dragged Mrs Lynde away. I must get ahead of the banker.

Mrs Braddock followed us to the door.

'And don't hurt Aunt Chatty's feelings, will you? Her feelings are so easily hurt. She's so sensitive, poor thing. You see, she hasn't quite as much money as Aunt Kate - though Aunt Kate hasn't any too much either. And then Aunt Kate liked her husband real well - her own husband, I mean - but Aunt Chatty didn't - didn't like hers, I mean. Small wonder! Lincoln MacLean was an old crank, but she thinks people hold it against her. It's lucky this is Saturday. If it was Friday Aunt Chatty wouldn't even consider taking you. You'd think Aunt Kate would be the superstitious one, wouldn't you? Sailors are kind of like that. But it's Aunt Chatty - although her husband was a carpenter. She was very pretty in her day, poor thing.'

I assured Mrs Braddock that Aunt Chatty's feelings would be sacred to me, but she followed us down the walk.

'Kate and Chatty won't explore your belongings when you're out. They're very conscientious. Rebecca Dew may, but she won't tell on you. And I wouldn't go to the front door, if I was you. They only use it for something real important. I don't think it's been opened since Amasa's funeral. Try the side-door. They keep the key under the flower-pot on the window-sill, so if nobody's home just unlock the door and go in and wait. And whatever you do don't praise the cat, because Rebecca Dew doesn't like him.'

I promised I wouldn't praise the cat, and we actually got away. Ere long we found ourselves in Spook's Lane. It is a very short side-street leading out to open country, and far away a blue hill makes a beautiful back-drop for it. On one side there are no houses at all, and the land slopes down to the harbour. On the other side there are only three. The first one is just a house. Nothing more to be said of it. The next one is a big, imposing, gloomy mansion of stone-trimmed red brick, with a mansard roof warty with dormer windows, an iron railing round the flat top, and so many spruces and firs crowding about it that you can hardly see the house. It must be frightfully dark inside. And the third and last is Windy Willows, right in the corner, with the grass-grown street on the front and a real country road, beautiful with tree shadows, on the other.

I fell in love with it at once. You know, there are houses which impress themselves upon you at first sight for some reason you can hardly define. Windy Willows is like that. I may describe it to you as a white frame house - very white - with green shutters - very green - with a 'tower' in the corner and a dormer window on either side, a low stone wall dividing it from the street, with willows growing at intervals along it, and a big garden at the back where flowers and vegetables are delightfully jumbled up together. But all this can't convey its charm to you. In short, it is a house with a delightful personality, and has something of the flavour of Green Gables about it.

'This is the spot for me. It's been foreordained,' I said rapturously.

Mrs Lynde looked as if she didn't quite trust foreordination. 'It'll be a long walk to school,' she said dubiously.

'I don't mind that. It will be good exercise. Oh, look at that lovely birch and maple grove across the road!'

Mrs Lynde looked, but all she said was, 'I hope you won't be pestered with mosquitoes.'

I hoped so too. I detest mosquitoes. One mosquito can keep me awaker than a bad conscience.

I was glad we didn't have to go in by the front door. It looked so forbidding - a big, double-leaved, grained-wood affair, flanked by panels of red flowered glass. It doesn't seem to belong to the house at all. The little green side-door, which we reached by a darling path of thin flat sandstones sunk at intervals in the grass, was much more friendly and inviting. The path was edged by very prim, well-ordered beds of ribbon grass and bleeding-heart and tiger-lilies and sweet-william and southernwood and bride's bouquet and red-and-white daisies and what Mrs Lynde calls 'pinies'. Of course, they weren't all in bloom at this season, but you could see they had bloomed at the proper time, and done it well. There was a rose-plot in a far corner, and between Windy Willows and the gloomy house next door a brick wall all overgrown with Virginia creeper, with an arched trellis above a faded green door in the middle of it. A vine ran right across it, so it was plain it hadn't been opened for some time. It was really only half a door, for its top half was merely an open oblong through which we could catch a glimpse of a jungly garden on the other side.

Just as we entered the gate of the garden of Windy Willows I noticed a little clump of clover right by the path. Some impulse led me to stoop down and look at it. Would you believe it, Gilbert? There, right before my eyes, were three four-leaved clovers! Talk about omens! Even the Pringles can't contend against that. And I felt sure the banker hadn't an earthly chance.

The side-door was open, so it was evident somebody was at home, and we didn't have to look under the flower-pot. We knocked, and Rebecca Dew came to the door. We knew it was Rebecca Dew because it couldn't have been anyone else in the whole wide world. And she couldn't have had any other name.

Rebecca Dew is 'around forty', and if a tomato had black hair racing away from its forehead, little twinkling black eyes, a tiny nose with a knobby end, and a slit of a mouth it would look exactly like her. Everything about her is a little too sh

ort - arms and legs and neck and nose, everything but her smile. It is long enough to reach from ear to ear. But we didn't see her smile just then. She looked very grim when I asked if I could see Mrs MacComber.

'You mean Mrs Captain MacComber?' she said rebukingly, as if there were at least a dozen Mrs MacCombers in the house.

'Yes,' I said meekly, and we were forthwith ushered into the parlour and left there. It was rather a nice little room, a bit cluttered up with antimacassars, but with a quiet, friendly atmosphere about it that I liked. Every bit of furniture had its own particular place which it had occupied for years. How that furniture shone! No bought polish ever produced that mirror-like gloss. I knew it was Rebecca Dew's elbow-grease. There was a full-rigged ship in a bottle on the mantelpiece which interested Mrs Lynde greatly. She couldn't imagine how it ever got into the bottle, but she thought it gave the room 'a nautical air'.

'The widows' came in. I liked them at once. Aunt Kate was tall and thin and grey and a little austere - Marilla's type exactly - and Aunt Chatty was short and thin and grey and a little wistful. She may have been very pretty once, but nothing is now left of her beauty except her eyes. They are lovely - soft and big and brown.

I explained my errand, and the widows looked at each other.

'We must consult Rebecca Dew,' said Aunt Chatty.

'Undoubtedly,' said Aunt Kate.

Rebecca Dew was accordingly summoned from the kitchen. The cat came in with her, a big fluffy Maltese, with a white breast and a white collar. I would have liked to stroke him, but, remembering Mrs Braddock's warning, I ignored him.

Rebecca gazed at me without the glimmer of a smile.

'Rebecca,' said Aunt Kate, who, I have discovered, does not waste words, 'Miss Shirley wishes to board here. I don't think we can take her.'

'Why not?' said Rebecca Dew.

'It would be too much trouble for you, I am afraid,' said Aunt Chatty.

'I'm well used to trouble,' said Rebecca Dew. You can't separate those names, Gilbert. It's impossible - though the widows do it. They call her 'Rebecca' when they speak to her. I don't know how they manage it.

Mistress Pat

Mistress Pat A Tangled Web

A Tangled Web Anne of Green Gables

Anne of Green Gables Further Chronicles of Avonlea

Further Chronicles of Avonlea Magic for Marigold

Magic for Marigold Pat of Silver Bush

Pat of Silver Bush Anne of Avonlea

Anne of Avonlea Anne of the Island

Anne of the Island The Blue Castle

The Blue Castle The Blythes Are Quoted

The Blythes Are Quoted Emily of New Moon

Emily of New Moon Rainbow Valley

Rainbow Valley Rilla of Ingleside

Rilla of Ingleside 07 - Rainbow Valley

07 - Rainbow Valley Anne of Green Gables (Penguin)

Anne of Green Gables (Penguin) Emily Climbs

Emily Climbs Emily's Quest

Emily's Quest A Name for Herself

A Name for Herself Anne of Windy Poplars

Anne of Windy Poplars The Complete Works of L M Montgomery

The Complete Works of L M Montgomery The Story Girl

The Story Girl Anne's House of Dreams

Anne's House of Dreams Jane of Lantern Hill

Jane of Lantern Hill Anne of Ingleside

Anne of Ingleside